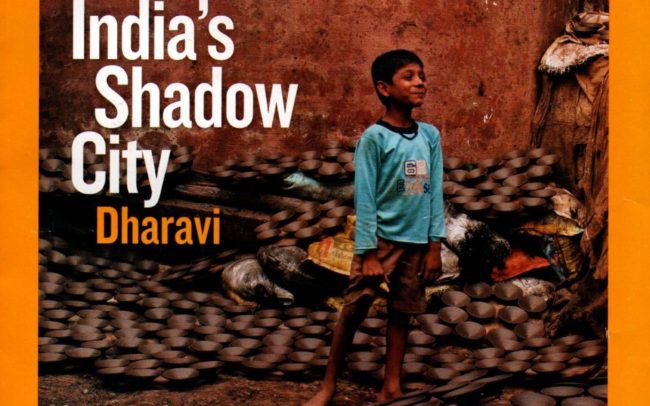

2007年、雑誌ナショナルジオグラフィックの5月号では、ムンバイにあるダラヴィという名の巨大スラムが特集されていた。スラムと言えば、公共サービスが行き届かず不衛生で治安が悪く、住民が貧困に喘いでいるというイメージを抱く人も多いかもしれない。でも、この特集はそんなイメージを容易に吹き飛ばすものであった。

The magazine, National Geographic May 2007, featured the gigantic slum Dharavi in Mumbai. Many might think that slum is the place that lacks sanitation and security due to no public services and people are crushed by poverty. The feature was one that easily change your stereotypical images on slum.

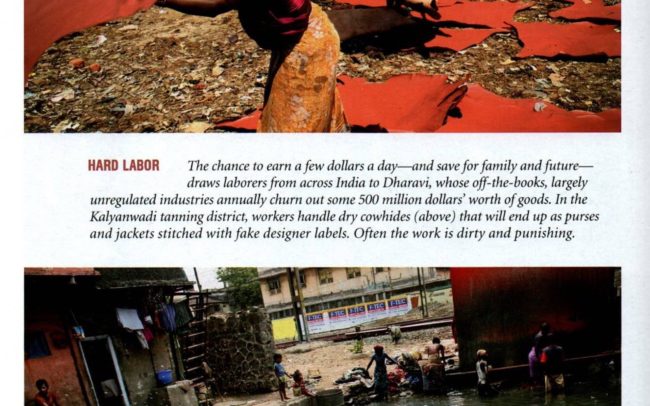

そこでは「A CITY WITHIN A CITY(街の中の街)」と題されてダラヴィの地図がページを大きく飾っていた。その地図は、このスラムのどこにどんな施設や産業があるかを示していた。このスラムにはこの当時で60万人もの住民が分け隔てない近所づきあいをしながら生活をしている。ここには、学校もあれば教会、モスクもある。それだけでなく、墓地や病院もある。そして、プラスチックリサイクル産業、製陶産業、テキスタイル産業、皮なめし産業などがあって、驚くほどの収益を上げている。これが、公共サービスがないにもかかわらず、このスラムが「街」と呼ばれる所以である。ここの住民は自分たちの住環境に誇りを持って暮らしていて、政府の立ち退きの指示にも断固反対している。まるでスラム全体が一つの労働組合の様だった。社会学者サスキア・サッセンはムンバイのこれらのインフォーマル産業がいかにグローバル経済を支えているかを強調している。

In the article, the map of Dharavi titled “A CITY WITHIN A CITY” was on the full page of the article. The map shows the locations and the types of facilities and industries. 6 hundred thousand inhabitants live in this slum and get along well with each other in their neighborhood. The slum has not only schools, churches and mosques but also graveyards and hospitals. Many small industries such as a plastics recycler, a pottery, a textile manufacturer, a tanner, etc., exist and make a surprising profit. This is why the slum is called “a city” although it does not have public services. The inhabitants are proud of their living environment and decisively opposed to the eviction order by the government. It seemed as if the whole slum was a labor union. A sociologist, Saskia Sassen, emphasizes that these informal industries essentially underpin the Global Economy.

住民が自分たちの生活を自力で築き上げ、その権利を外部権力にも怯まずに貫き通している。それも経済的な条件の悪い中で。そんなことが可能なのだということに驚いた。そして、どうすればそんなことが可能なのかを知りたいと思った。

The inhabitants build their lives by their own and stick to their right against the power outside. This is achieved under the economically bad condition. It was surprising that such a situation is possible. I was curious about how they make it.

建築学校を卒業したばかりだった僕は、クールな形態を追い求めるだけの建築業界や経済的合理性のみを追求する都市計画にうんざりしていて、自分の将来に暗澹たる気持ちでいた。でもこの特集を見て直ぐに、これこそが自分の生涯のテーマになると確信した。僕はいてもたってもいられず、3ヶ月後にムンバイに飛んだ。

I, who had graduated from an architectural school, had been bothered by the architectural industry which merely seeks outstanding forms and the urban planning which seeks only economical rationality. So at this time I was in the mood of gloomy about my future. I was convinced that this will be my lifework. I flew to Mumbai 3 months later.

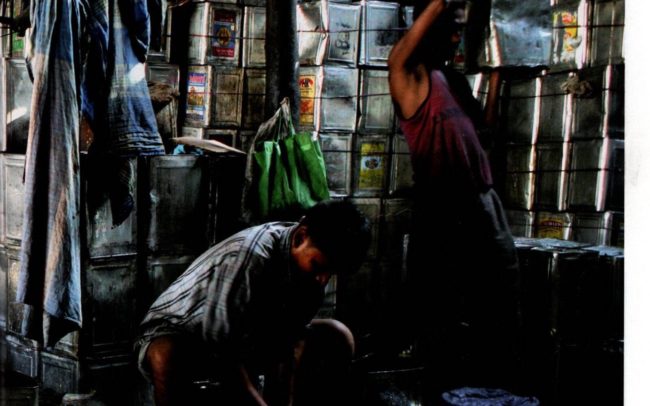

ムンバイに到着した僕は、まずは数日間あてどもなく街を歩き回った。ムンバイの街には、ダラヴィだけでなく小規模のスラムもマダラ模様のようにたくさんあり、インフォーマル産業や市場もひしめきあっていた。屋根のない青空の下で、汚れまみれで、ひどく狭い場所で、どんな条件の悪い場所でも、近代的な設備がなくても、創意工夫を凝らして商売を始める。そう言った特異な場所での商売が労働者どうしの人間関係を中世のギルドの様な特殊なものにしている様にも見えた。

As soon as I arrived, I strolled around the city and spent a few days to know about it. In Mumbai, not only Dharavi but also many small slums patchily exist. Informal industries and market are also vibrant. Under the sky without roof, with dirt, in a tiny space, in any unfavorable place, without modern facilities, people start their business. Their business under these conditions seemed to make their relationship unique like a guild in medieval times.

ダラヴィには小さなツアーが存在し、まずはそれに参加して見た。ツアーは写真撮影禁止で多少緊張感を伴うものであった。ただナショナルジオグラフィックで得た情報以上のものを得ることはできなかった。この後、個人でスラムを歩き回る技量は当時の僕にはなく、その後スラムの外周を30分ほど見て周って宿に帰った。けれども、この時の経験は今でも僕の頭から離れない。

I found the small tour for Dharavi and joined it. During the tour, photography was prohibited and I had a bit of strain feeling. Despite, I could not get more information than I got in National Geographic. I did not have skills to walk around slum personally. I, after the tour, just walked around the surrounding for about 30mins and went back to my hotel. However, the experience I had here is still vivid in my memories.

その数日後、ダラヴィの衛生面や治安の改善を中心に活動しているSPARKというNGO団体の事務所も訪問した。当時彼らは公衆トイレを作るプロジェクトなどを進めていた。担当者に、自分が建築を学んできた者だということを伝えた途端に彼の顔色が変わり、ダラヴィには建築家は必要ないと冷たい態度であしらわれた。ダラヴィの住人やNGOにとって、建築家は政府と同様に、住民の意を組まず自分たちの価値観を善意の名のもとに押しつけ、彼らの生活を破壊する者なのだと告げられた。当時の僕はこの担当者に「僕もその建築に腹を立てている一人なのだ」と反論することは出来なかった。なぜなら、自分から建築家という立場を捨ててしまったら、自分は何者としてスラムに携われば良いのか全く見当がつかなかったからだ。一体自分は何者なのだろうかと。その答えを得るまで、その後に随分長い年月とたくさんの人生経験が必要となった。

A few days later, I visited the NGO called SPARK which worked in the slum to improve sanitation and security. They were working on a public toilet project at this time. As soon as I told a staff that I was trained as an architect, he told me that an architect is not needed in Dharavi and continued that an architect is like the government, for the inhabitants and NGOs, who press their value on them under the word “development” and destroy their lives. I could not oppose telling her that I am also the one who was offended by architectural profession. It is because I could not tell how I involved in the slum if I parted with “an architect”. What in the world am I? Many years and variety of life experiences were needed for me until I got the answer.

初めてダラヴィを訪れてからおよそ10年の歳月を経て、1980年代にこのスラムの組合運動に携わっていた日本人と、それを組織していたダラヴィ生まれの活動家の存在を知ることになる。ようやくこのスラムが誕生したメカニズムの歴史的背景を知ることができたのだ。彼らのことについては、また別の機会に書きたいと思う。

10 years had passed since my first visit to Dharavi and I found the Japanese who was working for the union movement in this slum and the Dharavi born activist who organized the movement. Finally, I could know the historical background of mechanism which created this slum. I would write about them in another opportunity.

これからスラム学を構築して行くための現時点での僕の仮説であるけれども、スラムについて考えることは所得格差の問題について考えることだけではなく、近代建築が見逃してきた有機的な生活について考えることでもあり、またそれは近代家族とは違った家族のあり方について考えることでもある。にもかかわらず近代という仕組みから孤立することなしに、むしろ内側から近代を乗り越えて行こうとする試みでもある。これは、近代医学における東洋医学の立場に似ていると言えば、少しは分かりやすいかもしれない。

Although this is the hypothesis at this stage to build up slumics, thinking about slums means about not only the problem of income difference but also the organic lives that modern architecture has been ignoring and the style that is different from that of modern family. Despite, it is staying in and working with the system of Modernism and challenges to get over it from its inside. This can be likened to the relationship between modern medicine and oriental medicine.

スラムの問題は単なる経済だけの問題なのではなくて、経済と物質と感情が交差する場所に起きている問題である。だから、スラム学は貧しい住民たちの生活を経済的に少しでも楽にして行こうとする学問では決してない。スラム学とは、今後人口がますます増え続けるスラムの住民たちが、つまり富を持たぬ者たちが、協働で生活に必要な文化を築き上げそれによって権利を主張していくための技術を研究していく学問なのである。そして、ここで産み出される文化、それがスラムカルチャーなのである。

The problem of slum is not that of economy but one that is happening in the place where the problems of economy, material and emotion are overlaid. This is why slumics is not the study to challenge to make the poor inhabitants’ life easier economically. Slumics is the study to research into the technique to assert their rights with the culture that the increasing inhabitants of slum in population, so called the have-nots, cooperatively build up for their lives. This is called Slum Culture.

世界屈指の人口密度と言われるマカオ半島部の4分の1の面積に、マカオの全人口が居住している事を当てはめると理解し易い。

60万から100万の人口があればほぼほとんどの種類の職業や商売が存在しているのだろうし、外のエリアで働く「出稼ぎ」の割合も相当なものだろう。

フィリピン経済の4割は海外出稼ぎ組みからの送金で成り立っていると言われているが、何にしろ「出が多く入りが少ない」各国のスラムや貧区・発展途上エリアはいろんな面で富裕層に搾取されながらどこも同じようなサイクルで生活を維持させるのみで「貧」のスパイラルから抜け出せはしない。

特にインド周辺国には「カースト」や「階級制度」が未だ現存しては何代にも渡って繰り返される。

直面する問題は格差社会と宗教なのではないのか?

ダラヴィを見ていると香港の九龍城砦を連想する。

東京ドームの半分ほどの面積に5万人以上が住んでいたスラムは香港政庁の強権的な土地開発のための立ち退きで一気に取り壊されては「無」と化した。

実人口15億と言われるインドで100万人ほどの「ハリジャン」や背教徒のその後の人生など、国家や自治体にとってはインフラを整えるための方が重要だろう。

スラムと接する事はスピードの問題だ。